- Home

- Frederic Mullally

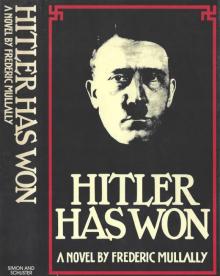

Hitler Has Won Page 4

Hitler Has Won Read online

Page 4

At these close quarters, with the early morning sun streaming through the tall window, the Doctor looked decidedly younger than his forty-four years, a curiously boyish figure, in fact, with his slight build, disproportionately large head and steeply sloping shoulders. He was favoring Kurt with a wide, almost conspiratorial smile.

“You won a bet for me yesterday, Armbrecht. And Reichsleiter Bormann is twenty marks the poorer for it. Emil,” he called over to the valet, “give the Captain a cup of coffee. And another half cup for me.”

They were alone now, except for the valet, standing by with a superbly cut dark-gray jacket at the ready while his master slipped a pair of cuff links into his cream-colored silk shirt. Kurt, balancing his coffee cup, had started to rise when Goebbels stepped down from the barber’s chair, but had been gestured to stay seated. And as the Doctor limped to his dressing table, Kurt was able to steal a swift glance at the inward-turning left foot, legacy of an operation after infantile paralysis at the age of four. It occurred to Kurt then that the Minister’s support for his appointment might have sprung from the fellow feeling of a cripple toward an amputee; therefore he was startled when Goebbels called over his shoulder, a second later, “That arm of yours—wouldn’t it help you in your work to have an artificial limb fitted?”

“I’m afraid not, Herr Doktor. There’s not really enough left of the humerus. But it doesn’t bother me at all, and I’ve doubled the speed of my Gabelsberger shorthand since you honored me with the interview in Munich.”

“Good, good.” The little figure was momentarily lost to view as Emil moved smoothly in with the jacket. “I’ve given up trying to persuade the Fuehrer to use a mechanical recorder. He won’t be in the same room with one. Which reminds me—” Goebbels was facing him once more, shooting a half-inch of cuff from his sleeve—“I have made arrangements with Reichsleiter Bormann for you to have access to the typescripts of all Heinrich Heim’s shorthand notes.”

“Heinrich Heim, Herr Doktor . . . ?”

“The official who has been recording the Fuehrer’s mealtime conversations since July of last year. His job is to take notes of the Fuehrer’s conversations with his guests, from an unobtrusive corner of the room. The notes are then dictated to a stenographer and go to Bormann for editing, annotation and so forth. I think you will find them quite valuable, Armbrecht.”

This was the opening Kurt had been hoping for. He said, rising and taking his cup over to the cart, “I am most indebted to you, Herr Doktor. I was hoping—perhaps a word or two of guidance from you as to the structure of the Fuehrer’s new book and the method I should follow?”

“The structure,” Goebbels said, frowning at his wrist watch, “will surely begin to suggest itself as the work progresses. I would put that out of your mind for the moment. As to method . . .” He was staring past Kurt, out of the window, softly gnawing at his sensual lower lip. “Perhaps we’d better go along to my study for five minutes. Emil, phone down to Herr Stimmer and tell him I shall be slightly delayed.”

Red had been the color used by Goebbels in all those pre-1933 posters aimed at the German working class. It was a color chosen by himself and Hitler as the circular background to the black swastika, a color deliberately stolen from the Communists, for its revolutionary message of urgency and violence. It was a color that stimulated rather than soothed, and as such, it seemed proper as the dominant color in the décor of the Propaganda Minister’s study. From the comfortable swivel chair behind the red-leather-topped desk, the Doctor could gaze over a vast expanse of red carpet toward the great fireplace at the other end of the room. Without turning his head, the cone of his vision would be encarmined by the lofty drapes of the window wall, muted symbols of those festive vertical banners that blazoned the Nazi charisma from the Fuehrer’s platform at every important prewar rally. Kurt was aware of smaller, subsidiary assertions of red here and there in the room but was unable, afterward, to give them an identity. His eyes had been drawn, almost immediately on entry, to the huge portrait of Adolf Hitler that took up most of the wall space behind Doctor Goebbels’s desk. It seemed at first the wrong place to hang a portrait of one’s mentor—out of one’s sight while working. But as the Doctor slipped into his chair and leaned back, propping his right knee up against the edge of the desk, the siting of the portrait made its own sense. Here in the forefront was Goebbels, the voice of the Party. And there, hugely behind him to remind any visitor of the source of this little man’s far-reaching authority, was the face and form of the Fuehrer, benignly presiding over every thought and action of his enfant prodige.

Kurt had lowered himself into one of the tall-backed chairs facing the Minister’s desk. Now, as Goebbels unbuckled his wrist watch to prop it—an unambiguous little ceremony—on the blotting pad, Kurt interpreted the Minister’s silence as his cue to open the dialogue.

“These notes of the Fuehrer’s mealtime conversations, Herr Doktor—I take it they are not for direct quotation in the new book?”

“They are for your reference, Armbrecht. They already run into many hundreds of typewritten pages and they embody the Fuehrer’s viewpoint on an immensely rich variety of subjects. They are no substitute, of course, for the considered statements the Fuehrer will be making to you about, for example, his plans for the new Germanic Empire.”

“These statements, Herr Doktor—presumably they are to be the main source material for the book?”

“Correct. But only within the framework of your own editing. This will involve the most scrupulous research on your part, so that no statement goes unsupported by the relevant historical or philosophical data. You will watch out for apparent contradictions, particularly by reference to the two books of Mein Kampf and to the Fuehrer’s speeches throughout his political career, and you will draw his attention to any such discrepancies. And it goes without saying that you will render the Fuehrer’s—um— expressive rhetoric into a literary idiom irreproachable as to grammar and general style.” He was now smiling openly at Kurt, offering the shared indulgence of two university graduates toward the scholastic deficiencies of a common associate. And Kurt returned a quick nervous smile, savoring for that brief moment a harmless irreverence he suspected would be a rare enough phenomenon in Chancellery circles and utterly unthinkable in the presence of Martin Bormann.

“This aspect of your work,” Goebbels went on, “the literary editing, is to be unobtrusive. You must see yourself not as a steamroller, ironing out the Fuehrer’s idiosyncratic language, but rather as a kind of cosmetic surgeon, delicately removing the warts and other blemishes from the otherwise strong and immensely distinctive features of your patient. You will find it helpful that the Fuehrer does not like having himself recorded, word for word, in shorthand. He will expect you to make a note of key statements, or his more eloquent turns of phrase, but he will not want to be addressing the top of your head during the private sessions. Give him plenty of attention as you commit to memory the conceptual nature of his pronouncements. When you are dismissed, whatever the time of day or night, there will be a stenographer on duty in the Fuehrer’s office to take immediate dictation, while your memory is still fresh. . . . Ah, yes, and at this particular time I would advise you to brief yourself thoroughly on Balkan and Middle-Eastern affairs. The Fuehrer is going to be greatly preoccupied over the next few months with the military and political solutions for these areas and it would be natural therefore that these will figure largely in his private discussions with you.

“Well, Captain—” Goebbels was reaching out for his wrist watch—“have I been of any help to you?”

“Immensely, Herr Doktor. I’m most indebted to you for sparing me your time.”

“We will go, then.” The slim figure was already limping toward the door.

As Kurt followed the Doctor down the staircase into the entrance hall, a man he recognized at once as Rudolf Stimmer, the aide who had taken him to Munich airport, snatched a briefcase from the side table and hurried to form a line with Emil,

who was bearing the Minister’s hat, overcoat and gloves, and Oven, who had the red briefcase grasped in both hands. There were, Kurt noticed, no “Heil Hitlers.” Goebbels nodded to his aides, took his hat and gloves from the valet, but declined the overcoat, whose very appearance seemed astonishing, considering the weather. Acknowledging the salutes of the police guard, he hurried down the steps toward the waiting Mercedes, smartly followed by Stimmer and Oven, with Kurt trailing uncertainly in the rear. A Nazi salute came from the chauffeur, standing at attention by the open door of the passenger seat up front. Stimmer and Oven took their places in the back of the car. Emil stepped forward carrying the Minister’s folded overcoat like a jeweler’s tray, and deposited it on one of the jump seats behind the driver, and the doors of the car were closed by the policeman. From his seat beside the chauffeur, Goebbels turned to raise a slim hand toward Kurt.

“Good luck, Captain.”

“Many thanks, Herr Doktor! Heil Hitler!”

Eight days went by before Kurt was summoned to his second meeting with Adolf Hitler. And while he awaited the call, busying himself with maps of the Balkans and the Middle East and the bulky briefings supplied by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Chancellery buzzed like a hive to the comings and goings of generals, admirals and Luftwaffe field marshals summoned to the day-and-night Fuehrer Conferences, each commander flanked by his personal retinue of solemn staff officers and keen-eyed adjutants and all of them activated by the whims and appetites of the exigent but invisible queen bee.

The news from the battlefields came like a daily—often hourly—shot of adrenaline. In Yugoslavia, the Croatian city of Zagreb, undermined by fifth columnists, had fallen to two Hungarian divisions, and the capital, Belgrade, had been isolated by Reichswehr panzer columns. The remains of the Yugoslav front-line armies were retreating toward the mountains, and the pro-German government-in-exile, whose overthrow in March 1941 had almost caused the enraged Hitler to postpone his attack on Russia, had already proclaimed from its headquarters in Budapest its intention of abolishing the monarchy and allying Yugoslavia to the Greater Reich.

The four armored divisions spearheading the invasion of Greece from Bulgaria had ripped through Salonika and were striking south toward Athens, leaving the British expeditionary forces with their backs to the Aegean and their one hope of salvation the British navy, now under murderous attack from Goering’s Luftwaffe and Raeder’s U-boats as it sailed out to the rescue from its last safe base in the Mediterranean, Alexandria.

Malta’s days were numbered. The island stronghold’s usefulness as a base from which to scatter and sink the convoys ferrying troops and supplies to Feldmarschall Rommel’s army in North Africa had ended three months ago, when five hundred of Goering’s bombers were switched from the eastern front to airfields in Sicily. Since then, not a single ship of the merchant convoys dispatched by Churchill through the Straits of Gibraltar had made anchorage in Malta’s Grand Harbour. The word around the Fuehrer’s office was that Malta and Crete would be taken before the end of the summer by paratroop divisions now training on the Italian island of Elba.

But the most exciting news of all during these eight days was coming from the Middle East. Rommel’s reinforced Afrika Korps was already bypassing Alexandria and pressing the British Eighth Army toward the Nile. Winston Churchill had just declared, in his most somber radio broadcast of the war:

Unless this new offensive can be halted and flung back, and our naval base in Alexandria relieved of jeopardy, we face the direst prospects. These would surely include the loss or, at best, the enforced withdrawal of our Eastern Mediterranean fleet, and with it the cutting of our lifeline between the Mediterranean and our empire in India. The vital oil resources of the Persian Gulf would be absorbed into the monstrous Nazi New Order. The continent of Africa would be fatally exposed to rape and plunder by Hitler’s Huns.

In the Chancellery canteen, where Kurt was now taking most of his meals, a great roar of derisive laughter had greeted the reading aloud of this monitored text by the Fuehrer’s interpreter, Paul Schmidt. To Kurt’s left, Heinrich Hoffman, Hitler’s official photographer, was choking, red-faced, over the third shot of Schnapps, swigged on the sly from his hip flask. “Think of it, Armbrecht,” he gasped, his thick Bavarian accent lending added vulgarity to the words, “all that virgin black meat just waiting to be ravaged by us Huns! Rommel’s lads are going to give a whole new meaning to the word schwarzfahren!”

The play on the German term for “joy-ride” won Hoffman a new explosion of guffaws, in which only Kurt and Julius Schaub, Hitler’s burly chief civilian adjutant, did not join.

“It’s not only in bad taste,” Schaub snapped when the laughter died down, “to suggest our soldiers would consort with savages. It’s also absurd to use the word ‘joy-ride’ in the same breath with Feldmarschall Rommel’s Afrika Korps. Have you no idea, Hoffman, of the conditions they are fighting under, and still have to face, before we can win the Middle East?”

Hoffman was scowling back, but holding his tongue. The lame, hard-drinking Bavarian had grown enormously rich from the Fuehrer’s patronage over these past twenty years, but he was completely outranked by SS Gruppenfuehrer Schaub, whose presence at the table was a rare enough event, made possible this day only because “the Chief”—as his closest aides referred among themselves to Hitler—was having a luncheon with Martin Bormann, Heinrich Himmler, and Karl Eichmann, head of the SS-controlled Jewish Office.

To take the heat off Hoffman, Kurt smoothly turned the conversation back to the Fuehrer’s lunchtime guests, the topic of discussion before Schmidt had stopped by with his translation of Churchill’s speech.

“I was wondering,” he inquired politely of Schaub, “how Obersturmbannfuehrer Eichmann fitted into the Fuehrer’s present preoccupations with the Balkans and the Middle East.”

“He doesn’t have to,” Schaub grunted. “The Fuehrer involves himself in everything, all the time.” And then, as though remembering his obligations toward the newcomer: “In this instance, however, there is a connection. It’s called Palestine.”

Kurt put down his fork, giving the chief adjutant his full attention.

“In the course of driving the British out of Arabia,” Schaub went on, “and linking up with Rundstedt’s forces in Persia, we shall be inheriting that dung heap called the Jewish National Home. It’ll be given back to the Arabs, of course, but the problem will remain of what to do with the Jews already infecting the territory.”

“The Grand Mufti will take care of that,” Hoffman chuckled. “Didn’t anyone read the report of his broadcast to the Arabs yesterday? ‘Kill the Jews wherever you find them,’ he said. ‘This pleases God, history and religion.’I’ll take abet . . ."

Kurt said, “But there must be half a million of them, including women and children. Where do we put them, now that we’ve promised the Arabs their land back?”

It seemed an obvious enough question, but suddenly they were all staring at him as if he had said something provocative. They stopped staring and made a pretense of getting on with their food—all except Hoffman, whose boozy eyes were now trained on Schaub. “Our young friend,” he said, breaking the silence, “has asked a question. Does the Herr Obergruppenfuehrer intend to answer it, or should I venture to give Armbrecht the facts of life?”

Julius Schaub emptied his coffee cup, shot Hoffman a look of withering animosity and rose noisily to his feet. “There are times when you bore the hell out of me, Hoffman,” he said through his teeth. And without another word, he swung around and stomped away across the room.

Kurt started to say, “Look, I don’t know what this is all about, but—”

“Pompous ass!” Hoffman shrugged, slipping his hip flask onto his lap. “And a moral coward on top of it.” He tossed back a silver stopperful of schnapps and released a soft, contented belch. “You’re one of us now, Armbrecht. We don’t have to mince words, do we?”

“I shouldn’t have thought so. But if I’m sticki

ng my nose into something I—” He broke off as Professor Morell, the Fuehrer’s physician, pushed his chair back and, with a mumbled “Good day, gentlemen,” made tracks for the door. This left Dr. Meissner, the Chancellery protocol chief, still at the table, and he was already folding his napkin and glancing pointedly at the canteen clock. Hoffman winked at Kurt and leaned back, staring up at the ceiling.

“Well, gentlemen, time I got back to the grindstone.” Meissner was on his feet, nodding and smiling.

“Naturally, Herr Doktor,” Hoffman grunted, still studying the ceiling. “Good day to you!”

The two men were alone now and out of earshot, while they kept their voices down, of the next tables. Hoffman offered Kurt a cigarette.

“Thanks, but I try not to smoke during the daytime.”

The photographer lighted his own, nodding. “Wise fellow, if you can keep it up. It’s murder when I’m on a job with the Chief. He once caught me having a quiet draw on the open terrace of the Berghof and bawled me out for fouling the air of Obersalzberg!”

“Getting back to that question of mine . . .”

“Ah, yes. The Palestine problem. Has nobody briefed you about Eichmann and the SS Special Action Groups?”

Hitler Has Won

Hitler Has Won