- Home

- Frederic Mullally

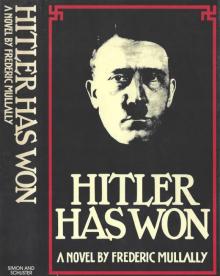

Hitler Has Won

Hitler Has Won Read online

Table of Contents

From The Dust Jacket

About The Author

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

AUTHOR'S NOTE

PEOPLE IN THE BOOK

From The Dust Jacket

This extraordinary novel is about Adolf Hitler—victorious! The time is March 1941, the place, the Fuehrer’s court. All Europe has been conquered—German troops have driven the defeated Russians beyond the Urals, Rommel’s armies are sweeping the British from Egypt, annihilating the Jews of Palestine, advancing victoriously on the Caucasus and on India. Triumphant, dazzled by the glory of his own victory, Hitler has called upon a maimed young Wehrmacht lieutenant to help him in a final historic task: the completion of volume two of Mein Kampf, the legacy of his victory to the 1000-Year Reich—Mein Sieg!

Through the young lieutenant’s astonished eyes we examine the incredible life of the inner circle of Nazi power—the devious machinations of Dr. Goebbels, the sinister, shadowy presence of Himmler and Bormann, the opulent debauchery of Goering—and share his startling discovery that the Fuehrer’s obsessions have led him to a final act of madness, a death struggle with the Catholic Church. This struggle gradually draws the lieutenant into a plot as fantastic and terrifying as any since that of The Manchurian Candidate, involving his beautiful young sister, a brutal SS officer, a Prince of the Church, and the Pope himself, and ending in the destruction of the Nazi state.

Brilliantly authentic in its descriptions of Nazi life and personalities, Hitler Has Won is, at the same time, a chilling, breathless and riveting work of fiction, a Hitchcock-style thriller set in the armies, palaces and camps of a triumphant Germany and centered on the fate of Adolf Hitler himself!

About The Author

Frederic Mullally was born in London of Irish parents. As a young journalist he worked his way to India on tramp ships where, at the age of nineteen, he became editor-in-chief of the Sunday Standard in Bombay. Subsequently he covered World War II as a reporter and did political writing until 1957, when he wrote his first novel, Danse Macabre, which became an immediate best seller in the United Kingdom. Since then he has written nine novels, one of which has been dramatized on the BBC.

Mr. Mullally is married to the British actress Rosemary Nicol and lives half the year on the island of Malta.

(Jacket design by Robert Anthony)

A list of real and fictitious characters appears at the back of the book.

Copyright © 1975 by Frederic Mullally

All rights reserved

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form

Published by Simon and Schuster

Rockefeller Center, 630 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10020

Designed by Irving Perkins

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Mullally, Frederic.

Hitler has won.

1. Hitler, Adolf, 1889-1945-Fiction.I. Title.

PZ4.M958Hi3 [PR6063.U38] 823'.9'14 75-11846

ISBN 0-671-22074-8

For

CLARENCE PAGET,

"bookman extraordinary"

But for a few elementary mistakes, he might have succeeded in conquering the world.—ROBERT PAYNE, The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler

If I could have added to my material power the spiritual power of the Papacy, I should have been the supreme ruler of the world.—NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

Mark my words, Bormann, I’m going to become very religious.—ADOLF HITLER, January 12, 1942

CHAPTER ONE

HE WAS standing at one of the tall gray-curtained windows, gazing out over the Chancellery gardens, as Kurt entered the room, keeping a respectful pace behind Martin Bormann. A man of about five feet nine, impressively erect for his fifty-three years, but with the thickened waist of a sedentary worker and a stealthy assertion of silver about the ears and above the closely trimmed neckline of his flat, dark-brown hair. The field-gray jacket and black trousers spoke of quality and a valet’s devotion, and as the man at the window turned briskly around, Kurt caught a glimpse of the Iron Cross, First Class, glinting low on the military pocket over the left breast before his eyes were pinned by the Fuehrer’s own swift and challenging stare.

“Heil Hitler!” He had diligently prepared his salute for this moment, so that the snap to rigid attention, the click of heels, the outflung arm would come as one smoothly integrated movement. And he had remembered the instructions of the head of the Party Chancellery, now advancing to the Fuehrer’s side. (“You will give him the German salute, not the military one. Don’t bawl it out like some overeager Kreisleiter. Just so long as it’s crisp and clearly audible. You will say nothing else until you are addressed.”)

“Lieutenant Armbrecht, my Fuehrer,” Bormann announced, half turning toward Kurt, who remained stiffly rooted to the carpet a few paces inside the salon. “His was the dossier the Doctor sent over this morning. If you would like to be reminded—” He broke off at a wave of the hand from Adolf Hitler.

“That won’t be necessary. I’ve read it. It’s all here.” The Fuehrer’s hand flicked on up, lightly brushing his right temple. “We shall have a. little chat. Lieutenant Armbrecht and myself.”

He hadn’t taken his eyes off Kurt since acknowledging his salute, and it was true what they said about the magnetism of that steady gaze. You were not being looked at or penetrated so much as being drawn by some invisible force burning behind the sallow, homely face of the most loved and most hated man in all the world. The spell was momentarily broken as Hitler muttered a few words of dismissal to Martin Bormann, only to be renewed as soon as Kurt, in quick response to the Fuehrer’s gesture, lowered himself into one of the hard-sprung leather armchairs and was once more held by that deep hypnotic stare.

“Two years ago you sacrificed an arm for your country. . . .” The voice was harsh but expressive, recalling for Kurt, subliminally, the accents of the athletic coach at his high school. It was a voice he had heard, through one medium or another, hundreds of times in the past ten years, but almost always impassioned and always amplified by loudspeakers or newsreel sound tracks. Here, in one of the smallest salons of the Chancellery’s ground floor, across the few yards of hand-woven carpet separating Kurt from Hitler, the famous voice, in this lower and unstrained register, was giving off cadences quite unfamiliar to Kurt. “Compelling” would be one word to describe it. And instantly one grasped the phenomena of Neville Chamberlain’s rushing back to England with his idiotic “Peace in our time,” of the aged President von Hindenburg’s blessing on the man who would bend and if necessary break the old Germany of inept parliamentarianism to his will.

“. . . would you now be willing to give up two, maybe three years of your private life to an enterprise that will bring no glory, no medals, no recognition apart from my own personal gratitude?”

“No German could dream of a richer reward, my Fuehrer.” The quiet statement came out of him unmeditated, like a received truth, flawless and inviolate.

Acknowledging it with the slightest dip of his head, the Fuehrer continued. “There will of course be some material compensations. The person I choose is to receive the pay and allowances of a captain in the Home Army throughout his employment and will be quartered and messed

here in the Chancellery, or at the Berghof, or wherever my movements take me. But there is another consideration, and I should be disappointed if a young man of your intelligence hadn’t already taken it into account.” He had started to measure, with precise, catlike steps, an area of carpet in front of the gray-curtained windows, but now he paused to favor Kurt with an almost roguish smile. “My literary secretary need not be too envious of the enormous royalties that will accrue to his Fuehrer from the sales of this sequel to Mein Kampf. He will be my automatic choice—assuming his work has pleased me—as official biographer of Adolf Hitler, whose death will therefore make him a millionaire. Have you not thought of that?”

He stopped abruptly, expecting a reply. Waiting for it. In the brief silence, Kurt’s mind swiftly framed and instinctively rejected two distinct but equally insincere answers, saying instead, “I hadn’t thought of it, my Fuehrer; and I’d rather not think about it now.”

“You’re a young man,” Hitler muttered, “and I shan’t live forever. Allow me to give you some facts about Mein Kampf.” He had resumed his pacing. “From 1925 to 1933, I lived on the royalties from that book and never had to draw a pfennig from Party funds. Since 1933, when I became Chancellor, the book has never failed to sell a million copies annually. But it has become almost a source of embarrassment to me, Armbrecht, and I shall tell you why. The book was dictated by me to that lunatic Hess in far too much of a hurry. I am an artist, you understand, and an orator, but I make no claims to being a graceful writer. Later, when the first draft was completed, I permitted that renegade Hieronymite priest, Bernhard Stempfle, to edit the typescript, and I will not deny that he put a polish on some of the rougher passages resulting from the speed of my dictation. But seventeen years have elapsed since Mein Kampf burst like a comet across the political firmament, and although it remains the philosophical cornerstone, so to speak, of my world outlook, there is a great deal in the testament that events and the passage of time have now made invalid. Alas, I have no doubt—” Hitler stopped his pacing to direct another wry smile at Kurt—“that there is a great deal that could, and perhaps should have been put more felicitously.”

Kurt started to protest, but was gestured back to silence.

“Don’t spoil the good impression you’ve already made on me, Armbrecht. Mein Kampf, along with Plato’s Republic, the Bible, and Marx’s Das Kapital, is one of the four unique books that have most influenced mankind. But, like the other three, it is a flawed work. So much so that my first intention, after I had watched our bulldozers level the ruins of the Kremlin to the ground at the beginning of this year, was to take a month off from the supreme command of the Wehrmacht, lock myself up in the Berghof at Obersalzberg, and devote myself to a completely revised edition of the two volumes. It was Reichsminister Goebbels who dissuaded me from this course. ‘The document you gave the world in 1925,’ he told me, ‘now belongs to history. Future generations will study it for the light it throws on the mind of Adolf Hitler as he stood on the threshold of power, challenging the enemies of Germany to do battle.’ But Mein Kampf, the Doctor went on to argue, must be read as the introduction to a work that will constitute my true epitaph. This work will explain, for the benefit of future historians, how a man of the people, a self-educated former corporal in the German army, managed in eight short years to raise a demoralized and bankrupt nation to be the masters of a Germanic empire stretching from Brest on the Atlantic to the Volga, from the North Cape to the Mediterranean.

“And it will prescribe, in definitive detail, the conditions that will guarantee the survival of Adolf Hitler’s New Order for the next thousand years. It will be the story of an incredible victory —a victory over the past, over the present, over the future. And there can be only one title—the Doctor and I agreed—for this work.” Hitler swung around on one heel of his brilliantly polished black shoes to face Kurt. His body became suddenly rigid, and the sagging facial muscles had contracted to reproduce in the flesh that stern and ubiquitous portrait of Der Fuehrer that had by now superseded the image of Christ for the millions of Kurt’s generation. There was a glint of teeth below the neatly squared-off mustache as the next two words ripped out like splinters of steel.

“Mein Sieg!”

In the same instant Kurt was up out of his chair and fighting for balance as his right arm shot forward to the cry, “Sieg Heil!” Without the balance of a left arm, the involuntary force of the reflex would have sent him sprawling had Hitler not stepped forward and crooked a stiff forearm for Kurt to seize. For a long moment they remained linked in silence, the twenty-seven-year-old disabled lieutenant and the ruler of all Europe and Russia-in-Europe. Kurt, who had dared to put his hand to the Fuehrer’s person, now dared not withdraw it without a sign.

The arm within the fine worsted yarn of Hitler’s gray sleeve untensed itself, freeing Kurt’s frozen hand.

“You are a good soldier, Armbrecht. I shall ask my personal surgeon, Dr. Karl Brandt, to have a look at your arm. Our German doctors are performing miracles with prosthesis these days. Sit down.”

Kurt had been sitting bolt upright for more than a quarter of an hour, breathing shallowly and willing his brain to memorize every word of Hitler’s monologue, delivered for the most part with didactic calm but erupting occasionally into scornful or triumphant declamation.

He had assumed that his first interview by the Fuehrer would have been brief. A few questions, maybe, about his already well-documented background, just to get him talking. A word or two about what would be expected of him in the almost inconceivable event that he be chosen for the post of Literary Assistant. But he had been asked no questions so far and, apart from the opening references to Mein Kampf and its projected sequel, there had been no pronouncement about the working method envisaged by the Fuehrer. Instead, Kurt Armbrecht was being honored with an inside account of Adolf Hitler’s masterly strategy, diplomatic and military, over the past tremendous year, the strategy that had won him his greatest victory. It was as if the Fuehrer had already made his decision, without waiting to interview the last candidates on Reichsminister Goebbels’s short list, and that he and Kurt were now launched on their first session together as narrator and scribe. Perhaps a miracle would occur and the time would come when he would be privileged to listen and take notes at the same time. For the moment, it was enough to listen, to memorize. . . .

“Consider the situation that faced me by the middle of January, 1941. I had already set a firm date for the spring invasion of Russia—May 15. The last thing I wanted was to stir up the neutral Balkan States. But Mussolini, without consulting me, had invaded Albania and Greece three months earlier and been given a bloody nose for his pains. On top of that, his North African army had been flung back from Egypt by the British and was now being chased back to Libya. I tell you, Armbrecht, with only four months to go before the launching of the greatest offensive in the history of warfare, I had no appetite for a Balkan campaign plus an operation in Libya. Yet something had to be done to contain the British during the six months it would take me to destroy the Red armies west of Moscow.

“I had the power to crush Greece and to halt and destroy Wavell’s army in North Africa. But of what use is the exercise of power unless as an integral part of a grand design?”

Hitler paused once again, staring out over the manicured Chancellery gardens, and Kurt seized the opportunity, without taking his eyes off the Fuehrer’s back, to ease himself into a slightly more comfortable position.

“There was deep snow blanketing Obersalzberg that day in January, when I summoned my military chiefs to a council of war at the Berghof,” the Fuehrer went on, his back still turned to the room. “I had slept on my decisions overnight, and when I took the air on the terrace that morning and looked out over those eternal Alpine peaks, I knew beyond all doubt that these decisions were inspired and therefore irrevocable.

“My instructions were as follows: Three divisions of the Reichswehr would be sent to Albania to stiffen the Itali

an forces along the Greek frontier, and to secure the main mountain passes between Albania and Yugoslavia. Ten divisions would be moved from Rumania into Bulgaria, where they would take up battle positions along the Yugoslav and Greek frontiers. Three panzer divisions under the command of General Rommel—as he was then—would be dispatched to Tripoli to hurl the British back into Egypt. There would be no invasion of Greece or Yugoslavia. Meantime squadrons of Reichsmarschall Goering’s Luftwaffe, operating from Libyan airfields, together with Admiral Raeder’s U-boats, would bottle up the British navy in Alexandria. Do you follow my brilliant strategy, Armbrecht?” He had turned from the window and his chin was up, his eyes flashing.

“Mein Fuehrer—”

“Impeccable!” Hitler clapped his hands together and chuckled as he renewed his carpet pacing. “Defensive positions everywhere. No excuse for Turkey to become alarmed. No excuse for Stalin, with his bandit eyes on the Bosporus and the Dardanelles, to send that robot of his, Molotov, scurrying to Berlin with hypocritical protests. But, most important of all, my armies on the eastern front could go ahead with their massive buildup for Operation Barbarossa. That date, May 15, 1941, was absolutely vital, Armbrecht, and would brook no postponement. It gave me a bare six months to encircle and destroy four hundred Bolshevik divisions and to reach Moscow before the winter clamped down. I say without hesitation, looking back over that shattering but glorious campaign, that if I had permitted a Balkan adventure to delay the invasion of Russia by as much as two weeks, we should still be grappling with the Russians west of Moscow.

“Instead, what is the situation today, thirteen months after the launching of Barbarossa? Marshal Timoshenko’s armies utterly destroyed. Advance columns of the Waffen-SS two hundred miles east of Moscow and threatening Gorki. Stalin cowering in Kubyshev. Four million Russian prisoners of war put to work building an impregnable system of defenses from Archangel to the Caspian Sea. Rail communications to Vladivostok cut off.

Hitler Has Won

Hitler Has Won